Hannah Paulson·August 29, 2023

The line-up of people waiting for airlift evacuation at Yellowknife’s Sir John Franklin High School around 11am on Thursday, August 17. Photo: Sándor Vörös

NationTalk: In the days leading up to Yellowknife’s evacuation, Tłı̨chǫ Grand Chief Jackson Lafferty says, the NWT government likely knew an evacuation order was imminent – or at least a real possibility.

Yet he says the Tłı̨chǫ Government was neither consulted, nor asked where more than 900 of its members who live in the area should go, or how they could be supported. “We could have assisted them,” Lafferty told Cabin Radio last week. “They are a treaty partner … but they didn’t even consider us.”

More: MLA wants Indigenous governments involved in emergency decisions

At the time, only 110 Tłı̨chǫ citizens had registered for evacuee services, leaving the whereabouts of around 800 people unclear. The territorial government has sent evacuees to at least three provinces, including hospital patients to BC, many evacuees to cities across Alberta, and some by air to Winnipeg.

The Tłı̨chǫ Government says it has stepped in to develop its own resource team and support its people.

“We look after our family, and that’s what we’re doing, as Tłı̨chǫ citizens,” Lafferty said, describing the work as starting from scratch by taking countless calls and emails, then trying to find those that are lost or may be in need of help.

Lafferty said he worried for the safety and well-being of vulnerable people. For some evacuees, this may be the first time they have left the territory, and navigating urban centres can come with challenges. For example, Lafferty said, some Elders have not had access to language services or interpreters.

At a press conference last week, NWT Premier Caroline Cochrane acknowledged that tracing all evacuees was “going to be a difficult process.”

As people were leaving, Cochrane said, nobody asked any evacuee “to identify themselves as homeless.” Now, the premier says her government is working with Indigenous governments and other organizations to identify people who may be at risk.

Lafferty, though, is frustrated by the lack of engagement – not only with the Tłı̨chǫ Government, but also other First Nations. “It’s not only us,” he said.

‘Our families have been disrupted’

Dene National Chief Gerald Antoine says the pain of relocation and displacement is not new to the Dene. “It has also been our experience with residential school and colonization,” Antoine said at a press conference on Friday.

Calling for the well-being of families and communities to be the top priority, Antoine said decisions in future should be grounded in the teachings of Elders and the land.

At the same press conference, Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation Chief Kele Antoine called for a renewed emergency and evacuation policy. “We need to do better,” he said.

Lisa Thurber, the founder of an NWT tenants’ association, has joined community-led efforts to help people who don’t know how to navigate the many layers of administration involved in the ongoing evacuation.

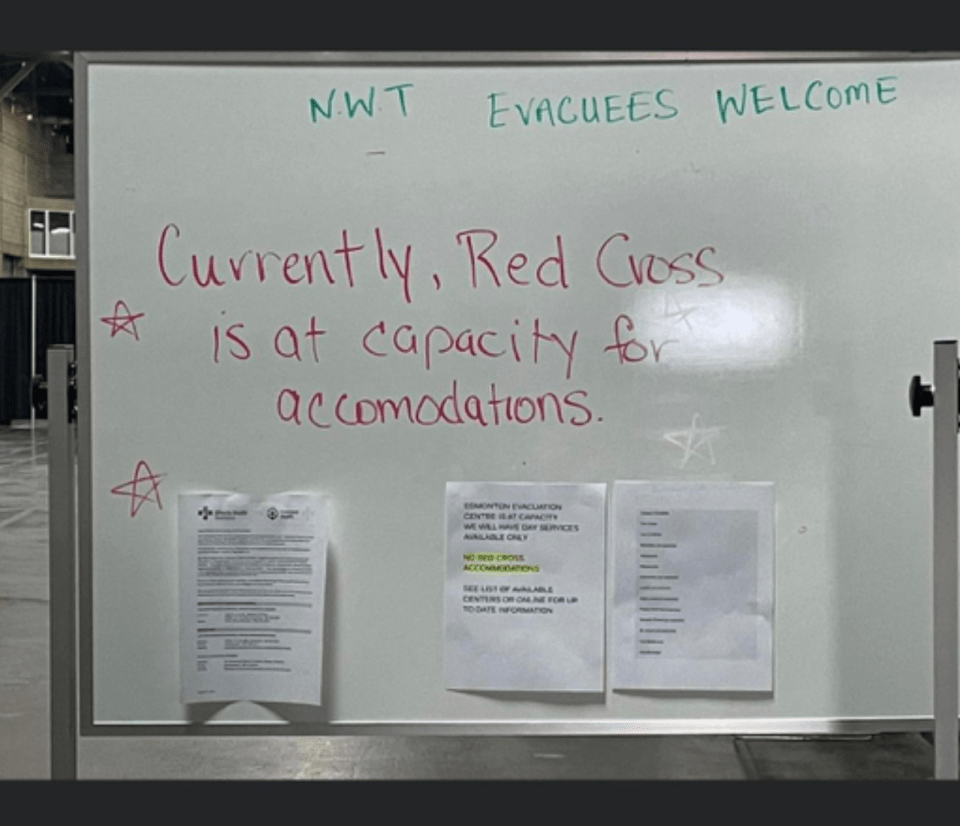

Thurber says the evacuation was “chaotic” and questions what is being done to support vulnerable people “dropped off” in large urban centres, drastically different from their home communities.

“Did they take into account the fact that these people would need special cultural attention? That they would need language services?” Thurber asked, querying whether those considerations were meaningfully factored into the emergency plan and subsequent evacuation.

“I don’t think [southern] jurisdictions in themselves have the capacity to handle their own local issues, let alone to deal with the unique needs of our NWT residents,” she added.

During a Friday press conference with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith, Cochrane – a social worker before she became the NWT’s leader – said she is aware of these concerns and shares them. “Many people have never been out of the territories and to think that they’re being put on the streets is scary. Scary, for me, as the premier – it must be petrifying for them,” Cochrane told reporters.

The premier said the two governments were working on solutions, saying she was glad the Alberta government had “recognized that, and there will be alternatives,” though the nature of those alternatives was not immediately clear.

Smith added: “We don’t want anyone to be on the street, so there’s a couple of options that we’re looking into.”

A spokesperson for the NWT government told Cabin Radio: “Since the GNWT does not have jurisdictional authority in Alberta, we are collaborating with the Government of Alberta to support the evacuation of NWT residents, and are ready should Alberta request our support.”

‘This might be our new reality’

More broadly, the past three years have seen residents of various NWT communities forced to flee their homes because of natural disasters like wildfires and flooding.

A recent report published by Indigenous Services Canada found Indigenous people are disproportionately displaced by wildfires, with 42 percent of evacuations occurring in Indigenous communities. Climate change is expected to increase the level of threat.

While many evacuees have praised the efforts of officials, communities and volunteers to help during the current crisis, some observers feel preparation for this eventuality was lacking. “There are a lot of people falling through the cracks in the system, and it just seems really very poorly planned,” said Katłįà Lafferty, a Yellowknives Dene author currently residing in Victoria while studying law.

Lafferty is supporting her mother, who Lafferty says was not able to receive the support she needed from governments at the time. “There could have been just so much done, proactively, to get ready for something like this,” she said, adding that leaders must realize the circumstances of this summer may not go away – and this may be “our new reality with climate change.”

“It’s sad to say, but we have to live in a way that we can adapt to it and be resilient to what’s coming, and what’s happening,” she said.

Lafferty says the current challenges facing communities can be partly traced to a disconnection from the way in which peoples traditionally related to and took care of the land in fluid, cyclical, and attentive fashion – through fire-burning practices, for example, or moving from place to place dependent on weather conditions.

“It’s just sad because we’ve been saying it for so long … to take care of the land, take care of the water, take care of the youth. Our future generations need the health of our land and water, and it’s just been ignored, and ignored, and ignored,” she said.

Lafferty recalled prophecies of fire found in the Book of Dene, which contains oral histories from Elders of the 16th and 17th centuries and has “stories of fire and sky people, how we existed, and how we came to be … and really amazing things that can be metaphors for what we’re going through today.”

“The beauty of our stories is that you can read them one way if you’re going through something and it will apply,” she said, “and then it can apply to something else if you read it a different way.”

The Mountain Which Melted

From The Book of Dene, a 1976 compilation of Dene oral histories prepared in Yellowknife by the territorial government.

The Old Man remade the earth.

All the men headed for the high ground. There they constructed a tall round tower.

“If there is ever another flood in the future, we shall be safe living in this building,” they said.

The tower was built on a mountain, close to the bitumen mines. Soon, the structure reached a great height.

The men building it began to make fun of one another’s language. “You speak a strange language. Your words are different from ours,” they said to each other.

Then, the ground began to tremble. The men were very frightened. Suddenly, the bitumen mines caught fire and exploded. There was a tremendous landslide.

Slowly, the mountain began to melt and the fire spread. Eventually, the mountain was no longer there. In its place was a vast, desolate plain, stretched as far as the eye could see.

The men had run away in all directions when the disaster struck. Now they were scattered all over the earth.

From that time on, men spoke different languages and no longer understood one another.

Related Articles

MLA wants Indigenous governments involved in emergency decisions August 29, 2023

‘We’re alone.’ Tłı̨chǫ Grand Chief says community resupply has broken down August 25, 2023

$24 million in funding announced for Hotıı̀ ts’eeda February 26, 2023